Friday, August 31, 2007

Thursday, August 23, 2007

Bushistory and Explaining Bush's Out of Body Experience

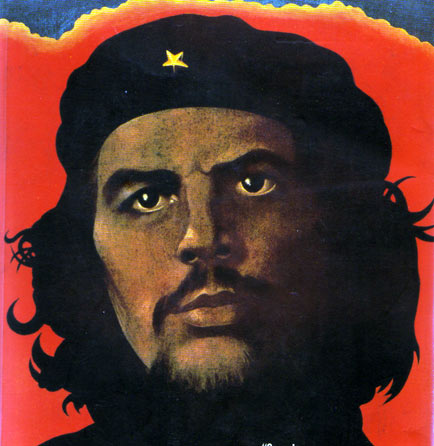

from Mike Luckovich

Behind Bush's Vietnam Revisionism

By Dan Froomkin

From the Washington Post

Thursday, August 23, 2007; 12:38 PM

President Bush's contentious speech on the recent history of American warfare yesterday was one element of a new White House PR campaign intended to solidify crumbling Republican congressional support for the war in Iraq and put Democrats on the defensive.

Bush's most controversial assertion -- that U.S. troops could have prevailed in Vietnam had they stayed longer -- is a neoconservative fantasy that almost all historians ridicule. But the overall campaign may still work.

Here's the text of the speech. I wrote about it at some length in yesterday's column.

How the Speech Was Made

Maura Reynolds and James Gerstenzang write in the Los Angeles Times: "With just three weeks to go before a crucial progress report on Iraq, the White House has launched a new communications effort to frame the debate by casting the war in historical terms. . . .

"Aides said the president felt it was necessary to revamp his message in the weeks before Army Gen. David H. Petraeus delivers a progress report that Congress mandated.

"White House counselor Ed Gillespie and Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove worked with the president on the speech. There was a sense in the White House that the president's rhetoric on Iraq, though consistent, was also becoming somewhat repetitive.

"'The repetition is necessary and by design,' White House communications director Kevin Sullivan said in an interview, adding that the language is usually fresh to every new audience. 'However, the president was aware of wanting to set the table for the upcoming report and the discussion that will follow it in a new way that was both compelling and illustrative. We've done this work before, and it was beneficial to the American people.'"

Reynolds and Gerstenzang quote a "former official who left the White House recently" as saying the president intentionally set out to turn a perceived weakness -- historical comparisons to Vietnam -- into a strength.

"'Vietnam has been wrung around the administration's neck on Iraq for a long time,' he said. 'There are many analogies or comparisons or connections that could cut against the administration's position, but this is a connection that supports the administration's position."

Ewen MacAskill writes in the Guardian: "The speech was aimed primarily at what White House officials privately describe as the 'defeatocrats', the Democratic Congressmen trying to push Mr Bush into an early withdrawal."

Richard Sisk writes in the New York Daily News: "A Republican source said White House strategists, believing anti-war Democrats will liken Iraq to the Vietnam War 'quagmire,' launched a preemptive strike 'to inoculate Bush.'"

But where did they get the idea that we should have stayed longer in Vietnam -- when the prevailing view is that we should have left earlier? (Or never have gone in to begin with?)

Farah Stockman and Bryan Bender write in the Boston Globe: "Many neoconservatives who helped shape the Bush administration's policies on Iraq have long argued that the United States was wrong to abandon the South Vietnamese in the war against the communist north. . . .

"To many in this circle, analysts say, the bitter lesson of Vietnam was not that the United States fought a misguided war, but rather that US troops withdrew too soon."

Stockman and Bender note that the argument first surfaced in an official White House speech in April, when Vice President Cheney spoke in Chicago to financial supporters and board members of the conservative Heritage Foundation. "Military withdrawal from Iraq, Cheney said, would trigger a replay of the same 'scenes of abandonment and retreat and regret' that followed the US military's departure from Vietnam. He likened recent Democratic calls for withdrawal to the 'far left' antiwar policies espoused by former senator George McGovern of South Dakota, the Democrats' nominee for president in 1972."

Changing the Political Dynamic

William Douglas and Margaret Talev write for McClatchy Newspapers: "President Bush stepped up his high-pressure sales job Wednesday to stay the course in Iraq, illustrating how the administration is both shifting the goalposts it once set for measuring success there and changing the political dynamic inside Congress on what to do about it."

And it may be going exactly as the White House had hoped.

"Bush now seems likely to prevail when Congress resumes wrestling about Iraq in September, for reports of limited military progress in Iraq have stiffened Republicans' support for Bush's policy while putting Democrats on the defensive. Without more Republican support, Democrats can't overcome Bush's veto power to force a change in policy. . . .

"Republicans said that reports of military progress in Iraq have greatly eased pressure on their members to abandon the war. They may even be able to put Democrats on the defensive."

But public opinion may not be as malleable as our public officials are. Opposition to the war in Iraq remains widespread, based on the amply supported conviction that things over there are a disaster. A few "good spin" days by the White House aren't going to change that.

Rejected By Historians

Bush argued that the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Southeast Asia three decades ago resulted in widespread death and suffering -- just as it would in Iraq. Historians and analysts were quick to refute this Vietnam revisionism.

As Stockman and Bender write in the Globe, political analysts and historians are agog.

"'I couldn't believe it,' said Allan Lichtman, an American University historian, adding that far more Vietnamese died during the war than in the aftermath of the US withdrawal. Lichtman said the rise of the Khmer Rouge, a brutal pro-communist regime, could as easily be attributed to American interference in that country.

"The president's portrayal of the conflict 'is not revisionist history. It is fantasy history,' Lichtman said.

"Melvin Laird, secretary of defense under President Nixon from 1969 to 1973, said Bush is drawing the wrong lessons from history.

"'I don't think what happened in Cambodia after the war has anything to do with Iraq,' Laird said. 'Is he saying we should have invaded Cambodia? That's what we would have had to do, and we would have never done that. I don't see how he draws the parallel.'

"Other historians said Bush bypassed the fact that, after the painful US withdrawal was completed in April 1975, Vietnam stabilized and developed into an economically thriving country that is now a friend of the United States."

Michael Tackett writes in the Chicago Tribune that Bush's remarks "invited stinging criticism from historians and military analysts who said the analogies evidenced scant understanding of those conflicts' true lessons. . . .

"'This was history written by speechwriters without regard to history,' said military analyst Anthony Cordesman. 'And I think most military historians will find it painful. . . . because in basic historical terms the president misstated what happened in Vietnam.' . . .

"Cordesman noted that human tragedies similar to those that occurred in the aftermath of U.S. involvement in Vietnam already have taken place in Iraq.

"'We are already talking about a country where the impact of our invasion has driven 2 million people out of the country, will likely drive out 2 million more, has reduced 8 million people to dire poverty, has killed 100,000 people and wounded 100,000 more,' he said. 'One sits sort of in awe at the lack of historical comparability.'

"It also struck some historians as odd that the president would try to use a divisive issue like Vietnam to rally the nation behind his policy in Iraq. 'If we get into a Vietnam argument, the country is divided, but if you are going to try sell this concept that the blood is on the American people's hands because we left and were weak-kneed in Asia, that is a very tenuous and inane historical argument,' said historian Douglas Brinkley."

The Associated Press quotes more reaction from experts:

"The speech was an act of desperation to scare the American people into staying the course in Iraq. He's distorted the facts, painting all of the people in Iraq as being on the same side which is simply not the case. Iraq is a religious civil war." -- Lawrence Korb, assistant defense secretary under President Reagan and now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington.

"Bush is cherry-picking history to support his case for staying the course. What I learned in Vietnam is that U.S. forces could not conduct a counterinsurgency operation. The longer we stay there, the worse it's going to get." -- Ret. Army Brig. Gen. John Johns, a counterinsurgency expert who served in Vietnam.

"The president emphasized the violence in the wake of American withdrawal from Vietnam. But this happened because the United States left too late, not too early. It was the expansion of the war that opened the door to Pol Pot and the genocide of the Khmer Rouge. The longer you stay the worse it gets." -- Steven Simon, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Opinion Watch

The New York Times editorial board writes: "The only lesson he found in the nation's last foreign quagmire of a war was that it ended too quickly."

The Los Angeles Times editorial board writes: "It's true that millions of Iraqi civilians have already paid a terrible price and may suffer even more as fighting may well worsen after a U.S. withdrawal -- whenever that occurs. But it seems equally clear that the civil war cannot be suppressed indefinitely unless the U.S. plans to occupy the country for decades. Killing fields? Iraq's already got them: A dozen or two corpses are found dumped in the streets each morning, and bombs go off daily. Boat people? Two million Iraqis have already fled the country, and perhaps 50,000 more leave each month. Could it get worse? Absolutely. But can we stop it?"

Here's David Gergen's reaction to the speech on CNN: "He's tried all along to say this is not Vietnam. By invoking Vietnam he raised the automatic question, well, if you've learned so much from history, Mr. President, how did you ever get us involved in another quagmire? Why didn't you learn up front about the perils of Vietnam and what we faced there? . . .

"But here's the other point, that if you look at Vietnam today, you have to say that Vietnam at the end, after 30 years, has actually become quite a driving country. It's a very strong economy. So there are those who say, yes, when we pull back there were bloodbaths in the immediate aftermath, but after that the Vietnamese started putting their country together. Is that not what we want Iraq to do over the long term? . . .

"[And] the other issue and why it's dangerous territory for him to go into Vietnam and the Vietnam analogy is reason we lost Vietnam in part was because we had no strategy. And the problem we've got now in Iraq, what is the strategy for victory? If the strategy for victory is let our troops give the Maliki government enough time to get everything solved, and the Maliki government is going nowhere, as everybody now admits, you know, what strategy are we facing? What strategy do we have to win in Iraq? It's not clear we have a winning strategy in Iraq. And that's what cost us Vietnam, and that's why we eventually withdrew under humiliating circumstances."

Here's Democratic strategist Paul Begala on CNN: "He's saying, essentially, that 58,000 dead in Vietnam weren't quite enough, that maybe we should have twice as big a tragic memorial on the Mall.

"And who's saying it? A man who chose not to serve, took steps, used family friends to get out of serving in Vietnam, didn't even show up for his own Guard duty, so that better, braver men could fight that war. He stood before those better, braver men today a coward in the company of heroes."

Sen. John Kerry released this statement: "Invoking the tragedy of Vietnam to defend the failed policy in Iraq is as irresponsible as it is ignorant of the realities of both of those wars. Half of the soldiers whose names are on the Vietnam Memorial Wall died after the politicians knew our strategy would not work. . . .

"As in Vietnam, we engaged militarily in Iraq based on official deception. As in Vietnam, more American soldiers are being sent to fight and die in a civil war we can't stop and an insurgency we can't bomb into submission. If the President wants to heed the lessons of Vietnam, he should change course and change course now."

A Change of Course

Researchers at the Senate Democratic Caucus chronicled the many times Bush himself has dismissed the Vietnam analogy, including this exchange at a press conference in April 2004:

"Q Thank you, Mr. President. Mr. President, April is turning into the deadliest month in Iraq since the fall of Baghdad, and some people are comparing Iraq to Vietnam and talking about a quagmire. Polls show that support for your policy is declining and that fewer than half Americans now support it. What does that say to you and how do you answer the Vietnam comparison?

"THE PRESIDENT: I think the analogy is false. I also happen to think that analogy sends the wrong message to our troops, and sends the wrong message to the enemy."

Loving Graham Greene?

Frank James blogs for the Tribune Washington bureau about yesterday's most bizarre moment by far: "In his speech at the Veterans of Foreign Wars convention in Kansas City today, President Bush summoned up the Alden Pyle CIA agent character of Graham Greene's classic Vietnam novel 'The Quiet American' which is essentially a contemplation on the road to hell being paved with good intentions.

"I'm not sure he really wanted to go there or why his speechwriters would take him there."

From Bush's speech: "In 1955, long before the United States had entered the war, Graham Greene wrote a novel called 'The Quiet American.' It was set in Saigon and the main character was a young government agent named Alden Pyle. He was a symbol of American purpose and patriotism and dangerous naivete. Another character describes Alden this way: 'I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.'

"After America entered the Vietnam War, Graham Greene -- the Graham Greene argument gathered some steam. Matter of fact, many argued that if we pulled out, there would be no consequences for the Vietnamese people."

As James writes: "Greene doesn't really help the White House's argument. Indeed, most people would read Greene's novel as a refutation of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. And why draw attention to a fictional character who has been used to outline Bush's alleged flaws....?"

By Dan Froomkin

From the Washington Post

Thursday, August 23, 2007; 12:38 PM

________________________________________

SCIENTISTS INDUCE OUT OF BODY [SOUL] EXPERIENCE:

from the The New York Times

August 23, 2007

Scientists Induce Out-of-Body Sensation

By SANDRA BLAKESLEE

Using virtual reality goggles, a camera and a stick, scientists have induced out-of-body experiences — the sensation of drifting outside of one’s own body — - in healthy people, according to experiments being published in the journal Science.

When people gaze at an illusory image of themselves through the goggles and are prodded in just the right way with the stick, they feel as if they have left their bodies.

The research reveals that “the sense of having a body, of being in a bodily self,” is actually constructed from multiple sensory streams, said Matthew Botvinick, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Princeton University, an expert on body and mind who was not involved in the experiments.

Usually these sensory streams, which include including vision, touch, balance and the sense of where one’s body is positioned in space, work together seamlessly, Prof. Botvinick said. But when the information coming from the sensory sources does not match up, when they are thrown out of synchrony, the sense of being embodied as a whole comes apart.

The brain, which abhors ambiguity, then forces a decision that can, as the new experiments show, involve the sense of being in a different body.

The research provides a physical explanation for phenomena usually ascribed to other-worldly influences, said Peter Brugger, a neurologist at University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. After severe and sudden injuries, people often report the sensation of floating over their body, looking down, hearing what is said, and then, just as suddenly, find themselves back inside their body. Out-of-body experiences have also been reported to occur during sleep paralysis, the exertion of extreme sports and intense meditation practices.

The new research is a first step in figuring out exactly how the brain creates this sensation, he said.

The out-of-body experiments were conducted by two research groups using slightly different methods intended to expand the so-called rubber hand illusion.

In that illusion, people hide one hand in their lap and look at a rubber hand set on a table in front of them. As a researcher strokes the real hand and the rubber hand simultaneously with a stick, people have the vivid sense that the rubber hand is their own.

When the rubber hand is whacked with a hammer, people wince and sometimes cry out.

The illusion shows that body parts can be separated from the whole body by manipulating a mismatch between touch and vision. That is, when a person’s brain sees the fake hand being stroked and feels the same sensation, the sense of being touched is misattributed to the fake.

The new experiments were designed to create a whole body illusion with similar manipulations.

In Switzerland, Dr. Olaf Blanke, a neuroscientist at the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, asked people to don virtual reality goggles while standing in an empty room. A camera projected an image of each person taken from the back and displayed 6 feet away. The subjects thus saw an illusory image of themselves standing in the distance.

Then Dr. Blanke stroked each person’s back for one minute with a stick while simultaneously projecting the image of the stick onto the illusory image of the person’s body.

When the strokes were synchronous, people reported the sensation of being momentarily within the illusory body. When the strokes were not synchronous, the illusion did not occur.

In another variation, Dr. Blanke projected a “rubber body” — a cheap mannequin bought on eBay and dressed in the same clothes as the subject — into the virtual reality goggles. With synchronous strokes of the stick, people’s sense of self drifted into the mannequin.

A separate set of experiments were carried out by Dr. Henrik Ehrsson, an assistant professor of neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Helsinki.

Last year, when Dr. Ehrsson was, as he says, “a bored medical student at University College London”, he wondered, he said, “what would happen if you ‘took’ your eyes and moved them to a different part of a room? Would you see yourself where you eyes were placed? Or from where your body was placed?”

To find out, Dr. Ehrsson asked people to sit on a chair and wear goggles connected to two video cameras placed 6 feet behind them. The left camera projected to the left eye. The right camera projected to the right eye. As a result, people saw their own backs from the perspective of a virtual person sitting behind them.

Using two sticks, Dr. Ehrsson stroked each person’s chest for two minutes with one stick while moving a second stick just under the camera lenses — as if it were touching the virtual body.

Again, when the stroking was synchronous people reported the sense of being outside their own bodies — in this case looking at themselves from a distance where their “eyes” were located.

Then Dr. Ehrsson grabbed a hammer. While people were experiencing the illusion, he pretended to smash the virtual body by waving the hammer just below the cameras. Immediately, the subjects registered a threat response as measured by sensors on their skin. They sweated and their pulses raced.

They also reacted emotionally, as if they were watching themselves get hurt, Dr. Ehrsson said.

People who participated in the experiments said that they felt a sense of drifting out of their bodies but not a strong sense of floating or rotating, as is common in full-blown out of body experiences, the researchers said.

The next set of experiments will involve decoupling not just touch and vision but other aspects of sensory embodiment, including the felt sense of the body position in space and balance, they said.

from the The New York Times

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Monday, August 20, 2007

The Iraq Obsession: Embracing Ignorance and the Politics of God

"Lahore, Pakistan - “I’ve promised myself I won’t go back to America until the Bush administration leaves . . . It’s hopeless with them there,” PostGlobal panelist and Taliban expert Ahmed Rashid tells me in his bulletproof library outside Lahore...

The administration has "actively rejected expertise and embraced ignorance," Ahmed told me inside his fortress. Soon after the Taliban fled Kabul in late 2001, Ahmed

visited Washington DC's policy elite as “the flavor of the month.” His bestseller Taliban had come out just the year before. The State Department, USAID, the National Security Council and the White House all asked him to present lectures on how to stabilize post-war Afghanistan.

Ahmed traversed the city’s bureaucracies and think tanks repeating “one common sense line”: In Afghanistan you have a “population on its knees, with nothing there, absolutely livid with the Taliban and the Arabs of Al Qaeda . . . willing to take anything.” The U.S. could "rebuild Afghanistan very quickly, very cheaply and make it a showcase in the Muslim world that says ‘Look U.S. intervention is not all about killing and bombing; it’s also about rebuilding and reconstruction…about American goodness and largesse.”

Many lifelong bureaucrats specializing in the region shared Ahmed's enthusiasm, and they agreed that after decades of violence, America could finally turn Afghanistan around through aid. But the biggest players in Bush's government, Ahmed says, had already shifted their attention to Iraq "abandoning Afghanistan at its moment of need." Read more here

_____________________________________________________

THE POLITICS OF GOD

"The twilight of the idols has been postponed. For more than two centuries, from the American and French Revolutions to the collapse of Soviet Communism, world politics revolved around eminently political problems. War and revolution, class and social justice, race and national identity — these were the questions that divided us. Today, we have progressed to the point where our problems again resemble those of the 16th century, as we find ourselves entangled in conflicts over competing revelations, dogmatic purity and divine duty. We in the West are disturbed and confused. Though we have our own fundamentalists, we find it incomprehensible that theological ideas still stir up messianic passions, leaving societies in ruin. We had assumed this was no longer possible, that human beings had learned to separate religious questions from political ones, that fanaticism was dead. We were wrong..."

"The Politics of God" can be read in its entirety here at The Washington Post

Sunday, August 19, 2007

Friday, August 17, 2007

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

Monday, August 13, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)