Click Here to See "2nd Term": Jib Jabbing The Bush

Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall...

Joe S. goes Ballistic:

Tribute to Molly Ivins: There are some Wise people in Texas

Nov. 19, 2002: "The greatest risk for us in invading Iraq is probably not war itself, so much as: What happens after we win? There is a batty degree of triumphalism loose in this country right now."

Jan. 16, 2003: "I assume we can defeat Hussein without great cost to our side (God forgive me if that is hubris). The problem is what happens after we win. The country is 20 percent Kurd, 20 percent Sunni and 60 percent Shiite. Can you say, 'Horrible three-way civil war?"'

Weeks Before She Died: "We are the people who run this country. We are the deciders. Every single day every single one of us needs to step outside and take some action to help stop this war. We need people in the streets banging pots and pans and demanding, 'Stop it now!' "

Worth Seeing Again: Good Christians Bearing Witness

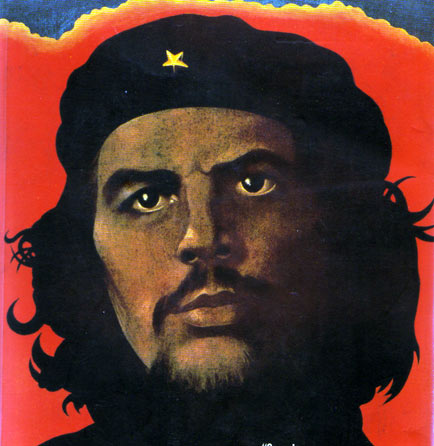

LOOK WHAT THE NEO-CONS HAVE GOTTEN US INTO!!!

NIE : NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE

Key Judgments

Iraqi society’s growing polarization, the persistent weakness of the security forces and the state in general, and all sides’ ready recourse to violence are collectively driving an increase in communal and insurgent violence and political extremism. Unless efforts to reverse these conditions show measurable progress during the term of this Estimate, the coming 12 to 18 months, we assess that the overall security situation will continue to deteriorate at rates comparable to the latter part of 2006. If strengthened Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), more loyal to the government and supported by Coalition forces, are able to reduce levels of violence and establish more effective security for Iraq’s population, Iraqi leaders could have an opportunity to begin the process of political compromise necessary for longer term stability, political progress, and economic recovery.

• Nevertheless, even if violence is diminished, given the current winner-take-all attitude and sectarian animosities infecting the political scene, Iraqi leaders will be hard pressed to achieve sustained political reconciliation in the time frame of this Estimate.

The challenges confronting Iraqis are daunting, and multiple factors are driving the current trajectory of the country’s security and political evolution.

• Decades of subordination to Sunni political, social, and economic domination have made the Shia deeply insecure about their hold on power. This insecurity leads the Shia to mistrust US efforts to reconcile Iraqi sects and reinforces their unwillingness to engage with the Sunnis on a variety of issues, including adjusting the structure of Iraq’s federal system, reining in Shia militias, and easing de-Bathification.

• Many Sunni Arabs remain unwilling to accept their minority status, believe the central government is illegitimate and incompetent, and are convinced that Shia dominance will increase Iranian influence over Iraq, in ways that erode the state’s Arab character and increase Sunni repression.

• The absence of unifying leaders among the Arab Sunni or Shia with the capacity to speak for or exert control over their confessional groups limits prospects for reconciliation. The Kurds remain willing to participate in Iraqi state building but reluctant to surrender any of the gains in autonomy they have achieved.

• The Kurds are moving systematically to increase their control of Kirkuk to guarantee annexation of all or most of the city and province into the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) after the constitutionally mandated referendum scheduled to occur no later than 31 December 2007. Arab groups in Kirkuk continue to resist violently what they see as Kurdish encroachment.

• Despite real improvements, the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF)—particularly the Iraqi police—will be hard pressed in the next 12-18 months to execute significantly increased security responsibilities, and particularly to operate independently against Shia militias with success. Sectarian divisions erode the dependability of many units, many are hampered by personnel and equipment shortfalls, and a number of Iraqi units have refused to serve outside of the areas where they were recruited.

• Extremists—most notably the Sunni jihadist group al-Qa’ida in Iraq (AQI) and Shia oppositionist Jaysh al-Mahdi (JAM)—continue to act as very effective accelerators for what has become a self-sustaining inter-sectarian struggle between Shia and Sunnis.

• Significant population displacement, both within Iraq and the movement of Iraqis into neighboring countries, indicates the hardening of ethno-sectarian divisions, diminishes Iraq’s professional and entrepreneurial classes, and strains the capacities of the countries to which they have relocated. The UN estimates over a million Iraqis are now in Syria and Jordan.

The Intelligence Community judges that the term “civil war” does not adequately capture the complexity of the conflict in Iraq, which includes extensive Shia-on-Shia violence, al-Qa’ida and Sunni insurgent attacks on Coalition forces, and widespread criminally motivated violence. Nonetheless, the term “civil war” accurately describes key elements of the Iraqi conflict, including the hardening of ethno-sectarian identities, a sea change in the character of the violence, ethno-sectarian mobilization, and population displacements.

Coalition capabilities, including force levels, resources, and operations, remain an essential stabilizing element in Iraq. If Coalition forces were withdrawn rapidly during the term of this Estimate, we judge that this almost certainly would lead to a significant increase in the scale and scope of sectarian conflict in Iraq, intensify Sunni resistance to the Iraqi Government, and have adverse consequences for national reconciliation.

• If such a rapid withdrawal were to take place, we judge that the ISF would be unlikely to survive as a non-sectarian national institution; neighboring countries—invited by Iraqi factions or unilaterally—might intervene openly in the conflict; massive civilian casualties and forced population displacement would be probable; AQI would attempt to use parts of the country—particularly al-Anbar province—to plan increased attacks in and outside of Iraq; and spiraling violence and political disarray in Iraq, along with Kurdish moves to control Kirkuk and strengthen autonomy, could prompt Turkey to launch a military incursion.

A number of identifiable developments could help to reverse the negative trends driving Iraq’s current trajectory. They include:

• Broader Sunni acceptance of the current political structure and federalism to begin to reduce one of the major sources of Iraq’s instability.

• Significant concessions by Shia and Kurds to create space for Sunni acceptance of federalism.

• A bottom-up approach—deputizing, resourcing, and working more directly with neighborhood watch groups and establishing grievance committees—to help mend frayed relationships between tribal and religious groups, which have been mobilized into communal warfare over the past three years.

A key enabler for all of these steps would be stronger Iraqi leadership, which could enhance the positive impact of all the above developments.

Iraq’s neighbors influence, and are influenced by, events within Iraq, but the involvement of these outside actors is not likely to be a major driver of violence or the prospects for stability because of the self-sustaining character of Iraq’s internal sectarian dynamics. Nonetheless, Iranian lethal support for select groups of Iraqi Shia militants clearly intensifies the conflict in Iraq. Syria continues to provide safehaven for expatriate Iraqi Bathists and to take less than adequate measures to stop the flow of foreign jihadists into Iraq.

• For key Sunni regimes, intense communal warfare, Shia gains in Iraq, and Iran’s assertive role have heightened fears of regional instability and unrest and contributed to a growing polarization between Iran and Syria on the one hand and other Middle East governments on the other. But traditional regional rivalries, deepening ethnic and sectarian violence in Iraq over the past year, persistent anti-Americanism in the region, anti-Shia prejudice among Arab states, and fears of being perceived by their publics as abandoning their Sunni co-religionists in Iraq have constrained Arab states’ willingness to engage politically and economically with the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad and led them to consider unilateral support to Sunni groups.

• Turkey does not want Iraq to disintegrate and is determined to eliminate the safehaven in northern Iraq of the Kurdistan People’s Congress (KGK, formerly PKK)—a Turkish Kurdish terrorist group.

A number of identifiable internal security and political triggering events, including sustained mass sectarian killings, assassination of major religious and political leaders, and a complete Sunni defection from the government have the potential to convulse severely Iraq’s security environment. Should these events take place, they could spark an abrupt increase in communal and insurgent violence and shift Iraq’s trajectory from gradual decline to rapid deterioration with grave humanitarian, political, and security consequences. Three prospective security paths might then emerge:

• Chaos Leading to Partition. With a rapid deterioration in the capacity of Iraq’s central government to function, security services and other aspects of sovereignty would collapse. Resulting widespread fighting could produce de facto partition, dividing Iraq into three mutually antagonistic parts. Collapse of this magnitude would generate fierce violence for at least several years, ranging well beyond the time frame of this Estimate, before settling into a partially stable end-state.

• Emergence of a Shia Strongman. Instead of a disintegrating central government producing partition, a security implosion could lead Iraq’s potentially most powerful group, the Shia, to assert its latent strength.

• Anarchic Fragmentation of Power. The emergence of a checkered pattern of local control would present the greatest potential for instability, mixing extreme ethno-sectarian violence with debilitating intra-group clashes.

No comments:

Post a Comment