STATE OF DENIAL

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

Friday, August 31, 2007

Thursday, August 23, 2007

Bushistory and Explaining Bush's Out of Body Experience

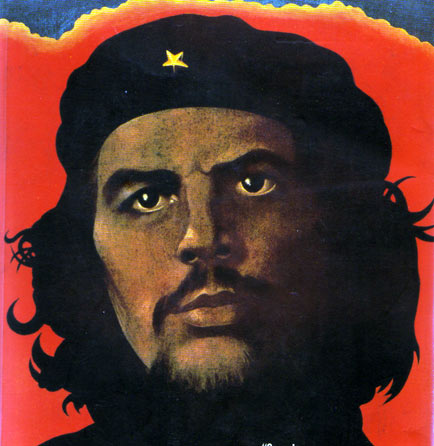

from Mike Luckovich

Behind Bush's Vietnam Revisionism

By Dan Froomkin

From the Washington Post

Thursday, August 23, 2007; 12:38 PM

President Bush's contentious speech on the recent history of American warfare yesterday was one element of a new White House PR campaign intended to solidify crumbling Republican congressional support for the war in Iraq and put Democrats on the defensive.

Bush's most controversial assertion -- that U.S. troops could have prevailed in Vietnam had they stayed longer -- is a neoconservative fantasy that almost all historians ridicule. But the overall campaign may still work.

Here's the text of the speech. I wrote about it at some length in yesterday's column.

How the Speech Was Made

Maura Reynolds and James Gerstenzang write in the Los Angeles Times: "With just three weeks to go before a crucial progress report on Iraq, the White House has launched a new communications effort to frame the debate by casting the war in historical terms. . . .

"Aides said the president felt it was necessary to revamp his message in the weeks before Army Gen. David H. Petraeus delivers a progress report that Congress mandated.

"White House counselor Ed Gillespie and Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove worked with the president on the speech. There was a sense in the White House that the president's rhetoric on Iraq, though consistent, was also becoming somewhat repetitive.

"'The repetition is necessary and by design,' White House communications director Kevin Sullivan said in an interview, adding that the language is usually fresh to every new audience. 'However, the president was aware of wanting to set the table for the upcoming report and the discussion that will follow it in a new way that was both compelling and illustrative. We've done this work before, and it was beneficial to the American people.'"

Reynolds and Gerstenzang quote a "former official who left the White House recently" as saying the president intentionally set out to turn a perceived weakness -- historical comparisons to Vietnam -- into a strength.

"'Vietnam has been wrung around the administration's neck on Iraq for a long time,' he said. 'There are many analogies or comparisons or connections that could cut against the administration's position, but this is a connection that supports the administration's position."

Ewen MacAskill writes in the Guardian: "The speech was aimed primarily at what White House officials privately describe as the 'defeatocrats', the Democratic Congressmen trying to push Mr Bush into an early withdrawal."

Richard Sisk writes in the New York Daily News: "A Republican source said White House strategists, believing anti-war Democrats will liken Iraq to the Vietnam War 'quagmire,' launched a preemptive strike 'to inoculate Bush.'"

But where did they get the idea that we should have stayed longer in Vietnam -- when the prevailing view is that we should have left earlier? (Or never have gone in to begin with?)

Farah Stockman and Bryan Bender write in the Boston Globe: "Many neoconservatives who helped shape the Bush administration's policies on Iraq have long argued that the United States was wrong to abandon the South Vietnamese in the war against the communist north. . . .

"To many in this circle, analysts say, the bitter lesson of Vietnam was not that the United States fought a misguided war, but rather that US troops withdrew too soon."

Stockman and Bender note that the argument first surfaced in an official White House speech in April, when Vice President Cheney spoke in Chicago to financial supporters and board members of the conservative Heritage Foundation. "Military withdrawal from Iraq, Cheney said, would trigger a replay of the same 'scenes of abandonment and retreat and regret' that followed the US military's departure from Vietnam. He likened recent Democratic calls for withdrawal to the 'far left' antiwar policies espoused by former senator George McGovern of South Dakota, the Democrats' nominee for president in 1972."

Changing the Political Dynamic

William Douglas and Margaret Talev write for McClatchy Newspapers: "President Bush stepped up his high-pressure sales job Wednesday to stay the course in Iraq, illustrating how the administration is both shifting the goalposts it once set for measuring success there and changing the political dynamic inside Congress on what to do about it."

And it may be going exactly as the White House had hoped.

"Bush now seems likely to prevail when Congress resumes wrestling about Iraq in September, for reports of limited military progress in Iraq have stiffened Republicans' support for Bush's policy while putting Democrats on the defensive. Without more Republican support, Democrats can't overcome Bush's veto power to force a change in policy. . . .

"Republicans said that reports of military progress in Iraq have greatly eased pressure on their members to abandon the war. They may even be able to put Democrats on the defensive."

But public opinion may not be as malleable as our public officials are. Opposition to the war in Iraq remains widespread, based on the amply supported conviction that things over there are a disaster. A few "good spin" days by the White House aren't going to change that.

Rejected By Historians

Bush argued that the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Southeast Asia three decades ago resulted in widespread death and suffering -- just as it would in Iraq. Historians and analysts were quick to refute this Vietnam revisionism.

As Stockman and Bender write in the Globe, political analysts and historians are agog.

"'I couldn't believe it,' said Allan Lichtman, an American University historian, adding that far more Vietnamese died during the war than in the aftermath of the US withdrawal. Lichtman said the rise of the Khmer Rouge, a brutal pro-communist regime, could as easily be attributed to American interference in that country.

"The president's portrayal of the conflict 'is not revisionist history. It is fantasy history,' Lichtman said.

"Melvin Laird, secretary of defense under President Nixon from 1969 to 1973, said Bush is drawing the wrong lessons from history.

"'I don't think what happened in Cambodia after the war has anything to do with Iraq,' Laird said. 'Is he saying we should have invaded Cambodia? That's what we would have had to do, and we would have never done that. I don't see how he draws the parallel.'

"Other historians said Bush bypassed the fact that, after the painful US withdrawal was completed in April 1975, Vietnam stabilized and developed into an economically thriving country that is now a friend of the United States."

Michael Tackett writes in the Chicago Tribune that Bush's remarks "invited stinging criticism from historians and military analysts who said the analogies evidenced scant understanding of those conflicts' true lessons. . . .

"'This was history written by speechwriters without regard to history,' said military analyst Anthony Cordesman. 'And I think most military historians will find it painful. . . . because in basic historical terms the president misstated what happened in Vietnam.' . . .

"Cordesman noted that human tragedies similar to those that occurred in the aftermath of U.S. involvement in Vietnam already have taken place in Iraq.

"'We are already talking about a country where the impact of our invasion has driven 2 million people out of the country, will likely drive out 2 million more, has reduced 8 million people to dire poverty, has killed 100,000 people and wounded 100,000 more,' he said. 'One sits sort of in awe at the lack of historical comparability.'

"It also struck some historians as odd that the president would try to use a divisive issue like Vietnam to rally the nation behind his policy in Iraq. 'If we get into a Vietnam argument, the country is divided, but if you are going to try sell this concept that the blood is on the American people's hands because we left and were weak-kneed in Asia, that is a very tenuous and inane historical argument,' said historian Douglas Brinkley."

The Associated Press quotes more reaction from experts:

"The speech was an act of desperation to scare the American people into staying the course in Iraq. He's distorted the facts, painting all of the people in Iraq as being on the same side which is simply not the case. Iraq is a religious civil war." -- Lawrence Korb, assistant defense secretary under President Reagan and now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington.

"Bush is cherry-picking history to support his case for staying the course. What I learned in Vietnam is that U.S. forces could not conduct a counterinsurgency operation. The longer we stay there, the worse it's going to get." -- Ret. Army Brig. Gen. John Johns, a counterinsurgency expert who served in Vietnam.

"The president emphasized the violence in the wake of American withdrawal from Vietnam. But this happened because the United States left too late, not too early. It was the expansion of the war that opened the door to Pol Pot and the genocide of the Khmer Rouge. The longer you stay the worse it gets." -- Steven Simon, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Opinion Watch

The New York Times editorial board writes: "The only lesson he found in the nation's last foreign quagmire of a war was that it ended too quickly."

The Los Angeles Times editorial board writes: "It's true that millions of Iraqi civilians have already paid a terrible price and may suffer even more as fighting may well worsen after a U.S. withdrawal -- whenever that occurs. But it seems equally clear that the civil war cannot be suppressed indefinitely unless the U.S. plans to occupy the country for decades. Killing fields? Iraq's already got them: A dozen or two corpses are found dumped in the streets each morning, and bombs go off daily. Boat people? Two million Iraqis have already fled the country, and perhaps 50,000 more leave each month. Could it get worse? Absolutely. But can we stop it?"

Here's David Gergen's reaction to the speech on CNN: "He's tried all along to say this is not Vietnam. By invoking Vietnam he raised the automatic question, well, if you've learned so much from history, Mr. President, how did you ever get us involved in another quagmire? Why didn't you learn up front about the perils of Vietnam and what we faced there? . . .

"But here's the other point, that if you look at Vietnam today, you have to say that Vietnam at the end, after 30 years, has actually become quite a driving country. It's a very strong economy. So there are those who say, yes, when we pull back there were bloodbaths in the immediate aftermath, but after that the Vietnamese started putting their country together. Is that not what we want Iraq to do over the long term? . . .

"[And] the other issue and why it's dangerous territory for him to go into Vietnam and the Vietnam analogy is reason we lost Vietnam in part was because we had no strategy. And the problem we've got now in Iraq, what is the strategy for victory? If the strategy for victory is let our troops give the Maliki government enough time to get everything solved, and the Maliki government is going nowhere, as everybody now admits, you know, what strategy are we facing? What strategy do we have to win in Iraq? It's not clear we have a winning strategy in Iraq. And that's what cost us Vietnam, and that's why we eventually withdrew under humiliating circumstances."

Here's Democratic strategist Paul Begala on CNN: "He's saying, essentially, that 58,000 dead in Vietnam weren't quite enough, that maybe we should have twice as big a tragic memorial on the Mall.

"And who's saying it? A man who chose not to serve, took steps, used family friends to get out of serving in Vietnam, didn't even show up for his own Guard duty, so that better, braver men could fight that war. He stood before those better, braver men today a coward in the company of heroes."

Sen. John Kerry released this statement: "Invoking the tragedy of Vietnam to defend the failed policy in Iraq is as irresponsible as it is ignorant of the realities of both of those wars. Half of the soldiers whose names are on the Vietnam Memorial Wall died after the politicians knew our strategy would not work. . . .

"As in Vietnam, we engaged militarily in Iraq based on official deception. As in Vietnam, more American soldiers are being sent to fight and die in a civil war we can't stop and an insurgency we can't bomb into submission. If the President wants to heed the lessons of Vietnam, he should change course and change course now."

A Change of Course

Researchers at the Senate Democratic Caucus chronicled the many times Bush himself has dismissed the Vietnam analogy, including this exchange at a press conference in April 2004:

"Q Thank you, Mr. President. Mr. President, April is turning into the deadliest month in Iraq since the fall of Baghdad, and some people are comparing Iraq to Vietnam and talking about a quagmire. Polls show that support for your policy is declining and that fewer than half Americans now support it. What does that say to you and how do you answer the Vietnam comparison?

"THE PRESIDENT: I think the analogy is false. I also happen to think that analogy sends the wrong message to our troops, and sends the wrong message to the enemy."

Loving Graham Greene?

Frank James blogs for the Tribune Washington bureau about yesterday's most bizarre moment by far: "In his speech at the Veterans of Foreign Wars convention in Kansas City today, President Bush summoned up the Alden Pyle CIA agent character of Graham Greene's classic Vietnam novel 'The Quiet American' which is essentially a contemplation on the road to hell being paved with good intentions.

"I'm not sure he really wanted to go there or why his speechwriters would take him there."

From Bush's speech: "In 1955, long before the United States had entered the war, Graham Greene wrote a novel called 'The Quiet American.' It was set in Saigon and the main character was a young government agent named Alden Pyle. He was a symbol of American purpose and patriotism and dangerous naivete. Another character describes Alden this way: 'I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.'

"After America entered the Vietnam War, Graham Greene -- the Graham Greene argument gathered some steam. Matter of fact, many argued that if we pulled out, there would be no consequences for the Vietnamese people."

As James writes: "Greene doesn't really help the White House's argument. Indeed, most people would read Greene's novel as a refutation of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. And why draw attention to a fictional character who has been used to outline Bush's alleged flaws....?"

By Dan Froomkin

From the Washington Post

Thursday, August 23, 2007; 12:38 PM

________________________________________

SCIENTISTS INDUCE OUT OF BODY [SOUL] EXPERIENCE:

from the The New York Times

August 23, 2007

Scientists Induce Out-of-Body Sensation

By SANDRA BLAKESLEE

Using virtual reality goggles, a camera and a stick, scientists have induced out-of-body experiences — the sensation of drifting outside of one’s own body — - in healthy people, according to experiments being published in the journal Science.

When people gaze at an illusory image of themselves through the goggles and are prodded in just the right way with the stick, they feel as if they have left their bodies.

The research reveals that “the sense of having a body, of being in a bodily self,” is actually constructed from multiple sensory streams, said Matthew Botvinick, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Princeton University, an expert on body and mind who was not involved in the experiments.

Usually these sensory streams, which include including vision, touch, balance and the sense of where one’s body is positioned in space, work together seamlessly, Prof. Botvinick said. But when the information coming from the sensory sources does not match up, when they are thrown out of synchrony, the sense of being embodied as a whole comes apart.

The brain, which abhors ambiguity, then forces a decision that can, as the new experiments show, involve the sense of being in a different body.

The research provides a physical explanation for phenomena usually ascribed to other-worldly influences, said Peter Brugger, a neurologist at University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. After severe and sudden injuries, people often report the sensation of floating over their body, looking down, hearing what is said, and then, just as suddenly, find themselves back inside their body. Out-of-body experiences have also been reported to occur during sleep paralysis, the exertion of extreme sports and intense meditation practices.

The new research is a first step in figuring out exactly how the brain creates this sensation, he said.

The out-of-body experiments were conducted by two research groups using slightly different methods intended to expand the so-called rubber hand illusion.

In that illusion, people hide one hand in their lap and look at a rubber hand set on a table in front of them. As a researcher strokes the real hand and the rubber hand simultaneously with a stick, people have the vivid sense that the rubber hand is their own.

When the rubber hand is whacked with a hammer, people wince and sometimes cry out.

The illusion shows that body parts can be separated from the whole body by manipulating a mismatch between touch and vision. That is, when a person’s brain sees the fake hand being stroked and feels the same sensation, the sense of being touched is misattributed to the fake.

The new experiments were designed to create a whole body illusion with similar manipulations.

In Switzerland, Dr. Olaf Blanke, a neuroscientist at the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, asked people to don virtual reality goggles while standing in an empty room. A camera projected an image of each person taken from the back and displayed 6 feet away. The subjects thus saw an illusory image of themselves standing in the distance.

Then Dr. Blanke stroked each person’s back for one minute with a stick while simultaneously projecting the image of the stick onto the illusory image of the person’s body.

When the strokes were synchronous, people reported the sensation of being momentarily within the illusory body. When the strokes were not synchronous, the illusion did not occur.

In another variation, Dr. Blanke projected a “rubber body” — a cheap mannequin bought on eBay and dressed in the same clothes as the subject — into the virtual reality goggles. With synchronous strokes of the stick, people’s sense of self drifted into the mannequin.

A separate set of experiments were carried out by Dr. Henrik Ehrsson, an assistant professor of neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Helsinki.

Last year, when Dr. Ehrsson was, as he says, “a bored medical student at University College London”, he wondered, he said, “what would happen if you ‘took’ your eyes and moved them to a different part of a room? Would you see yourself where you eyes were placed? Or from where your body was placed?”

To find out, Dr. Ehrsson asked people to sit on a chair and wear goggles connected to two video cameras placed 6 feet behind them. The left camera projected to the left eye. The right camera projected to the right eye. As a result, people saw their own backs from the perspective of a virtual person sitting behind them.

Using two sticks, Dr. Ehrsson stroked each person’s chest for two minutes with one stick while moving a second stick just under the camera lenses — as if it were touching the virtual body.

Again, when the stroking was synchronous people reported the sense of being outside their own bodies — in this case looking at themselves from a distance where their “eyes” were located.

Then Dr. Ehrsson grabbed a hammer. While people were experiencing the illusion, he pretended to smash the virtual body by waving the hammer just below the cameras. Immediately, the subjects registered a threat response as measured by sensors on their skin. They sweated and their pulses raced.

They also reacted emotionally, as if they were watching themselves get hurt, Dr. Ehrsson said.

People who participated in the experiments said that they felt a sense of drifting out of their bodies but not a strong sense of floating or rotating, as is common in full-blown out of body experiences, the researchers said.

The next set of experiments will involve decoupling not just touch and vision but other aspects of sensory embodiment, including the felt sense of the body position in space and balance, they said.

from the The New York Times

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Monday, August 20, 2007

The Iraq Obsession: Embracing Ignorance and the Politics of God

"Lahore, Pakistan - “I’ve promised myself I won’t go back to America until the Bush administration leaves . . . It’s hopeless with them there,” PostGlobal panelist and Taliban expert Ahmed Rashid tells me in his bulletproof library outside Lahore...

The administration has "actively rejected expertise and embraced ignorance," Ahmed told me inside his fortress. Soon after the Taliban fled Kabul in late 2001, Ahmed

visited Washington DC's policy elite as “the flavor of the month.” His bestseller Taliban had come out just the year before. The State Department, USAID, the National Security Council and the White House all asked him to present lectures on how to stabilize post-war Afghanistan.

Ahmed traversed the city’s bureaucracies and think tanks repeating “one common sense line”: In Afghanistan you have a “population on its knees, with nothing there, absolutely livid with the Taliban and the Arabs of Al Qaeda . . . willing to take anything.” The U.S. could "rebuild Afghanistan very quickly, very cheaply and make it a showcase in the Muslim world that says ‘Look U.S. intervention is not all about killing and bombing; it’s also about rebuilding and reconstruction…about American goodness and largesse.”

Many lifelong bureaucrats specializing in the region shared Ahmed's enthusiasm, and they agreed that after decades of violence, America could finally turn Afghanistan around through aid. But the biggest players in Bush's government, Ahmed says, had already shifted their attention to Iraq "abandoning Afghanistan at its moment of need." Read more here

_____________________________________________________

THE POLITICS OF GOD

"The twilight of the idols has been postponed. For more than two centuries, from the American and French Revolutions to the collapse of Soviet Communism, world politics revolved around eminently political problems. War and revolution, class and social justice, race and national identity — these were the questions that divided us. Today, we have progressed to the point where our problems again resemble those of the 16th century, as we find ourselves entangled in conflicts over competing revelations, dogmatic purity and divine duty. We in the West are disturbed and confused. Though we have our own fundamentalists, we find it incomprehensible that theological ideas still stir up messianic passions, leaving societies in ruin. We had assumed this was no longer possible, that human beings had learned to separate religious questions from political ones, that fanaticism was dead. We were wrong..."

"The Politics of God" can be read in its entirety here at The Washington Post

Sunday, August 19, 2007

Friday, August 17, 2007

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

Monday, August 13, 2007

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Friday, July 20, 2007

played for fools, again: Olbermann and more

The not-so-surprising judgement of the National Intelligence Estimate that Al Queda has reconstitued itself in western Pakistan drew an interesting response from the Bush Whitehouse that demands some thought. Bush's argument that Iraq is the main front in the "war on terror" is often supported by Al Queda's news releases that also argue the same--despite the fact that the military experts argue that only 10% of the violence and insurgency in Iraq is Al Queda. Why would Bin Laden say Iraq is the "main front" as he reconstitutes his base in Pakistan? Was this a strategy to keep us out of Pakistan? Maybe it is the main front for Osama because we're playing the fools for his game. Why shouldn't our "main front" be western Pakistan? And why do we continue to use Iraq as a stage upon which we battle Al Queda?

Thursday, June 14, 2007

Thursday, June 07, 2007

Wednesday, June 06, 2007

American Madrassa and the Evangelical Effect

The Evangelical Effect is the educational movement to a certain kind of "accountablity" focused on standardization and literalism, rather than creativity and metaphoric play, memorization over discovery, fear and moral exclusivity, over inclusive socialization: "numbers and letters", "good and evil."

"Universals" are those things and practices that have shared characteristics:

View these videos and then read the NY Times article on early childhood education:

And if you really want some food for thought, read Michael Foucalt's "Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison," on the subtle effects and mechanizisms of social and political power that form the "fundamental" principles underlying educational, military, and prison systems of "discplinary power".

NYTimes

June 3, 2007

When Should a Kid Start Kindergarten?

By ELIZABETH WEIL

According to the apple-or-coin test, used in the Middle Ages, children should start school when they are mature enough for the delayed gratification and abstract reasoning involved in choosing money over fruit. In 15th- and 16th-century Germany, parents were told to send their children to school when the children started to act “rational.” And in contemporary America, children are deemed eligible to enter kindergarten according to an arbitrary date on the calendar known as the birthday cutoff — that is, when the state, or in some instances the school district, determines they are old enough. The birthday cutoffs span six months, from Indiana, where a child must turn 5 by July 1 of the year he enters kindergarten, to Connecticut, where he must turn 5 by Jan. 1 of his kindergarten year. Children can start school a year late, but in general they cannot start a year early. As a result, when the 22 kindergartners entered Jane Andersen’s class at the Glen Arden Elementary School near Asheville, N.C., one warm April morning, each brought with her or him a snack and a unique set of gifts and challenges, which included for some what’s referred to in education circles as “the gift of time.”

After the morning announcements and the Pledge of Allegiance, Andersen’s kindergartners sat down on a blue rug. Two, one boy and one girl, had been redshirted — the term, borrowed from sports, describes students held out for a year by their parents so that they will be older, or larger, or more mature, and thus better prepared to handle the increased pressures of kindergarten today. Six of Andersen’s pupils, on the other hand, were quite young, so young that they would not be enrolled in kindergarten at all if North Carolina succeeds in pushing back its birthday cutoff from Oct. 16 to Aug. 31.

Andersen is a willowy 11-year teaching veteran who offered up a lot of education in the first hour of class. First she read Leo Lionni’s classic children’s book “An Extraordinary Egg,” and directed a conversation about it. Next she guided the students through: writing a letter; singing a song; solving an addition problem; two more songs; and a math game involving counting by ones, fives and tens using coins. Finally, Andersen read them another Lionni book. Labor economists who study what’s called the accumulation of human capital — how we acquire the knowledge and skills that make us valuable members of society — have found that children learn vastly different amounts from the same classroom experiences and that those with certain advantages at the outset are able to learn more, more quickly, causing the gap between students to increase over time. Gaps in achievement have many causes, but a major one in any kindergarten room is age. Almost all kindergarten classrooms have children with birthdays that span 12 months. But because of redshirting, the oldest student in Andersen’s class is not just 12 but 15 months older than the youngest, a difference in age of 25 percent.

After rug time, Andersen’s kindergartners walked single-file to P.E. class, where the children sat on the curb alongside the parking circle, taking turns running laps for the Presidential Fitness Test. By far the fastest runner was the girl in class who had been redshirted. She strode confidently, with great form, while many of the smaller kids could barely run straight. One of the younger girls pointed out the best artist in the class, a freckly redhead. I’d already noted his beautiful penmanship. He had been redshirted as well.

States, too, are trying to embrace the advantages of redshirting. Since 1975, nearly half of all states have pushed back their birthday cutoffs and four — California, Michigan, North Carolina and Tennessee — have active legislation in state assemblies to do so right now. (Arkansas passed legislation earlier this spring; New Jersey, which historically has let local districts establish their birthday cutoffs, has legislation pending to make Sept. 1 the cutoff throughout the state.) This is due, in part, to the accountability movement — the high-stakes testing now pervasive in the American educational system. In response to this testing, kindergartens across the country have become more demanding: if kids must be performing on standardized tests in third grade, then they must be prepping for those tests in second and first grades, and even at the end of kindergarten, or so the thinking goes. The testing also means that states, like students, now get report cards, and they want their children to do well, both because they want them to be educated and because they want them to stack up favorably against their peers.

Indeed, increasing the average age of the children in a kindergarten class is a cheap and easy way to get a small bump in test scores, because older children perform better, and states’ desires for relative advantage is written into their policy briefs. The California Performance Review, commissioned by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2004, suggested moving California’s birthday cutoff three months earlier, to Sept. 1 from Dec. 2, noting that “38 states, including Florida and Texas, have kindergarten entry dates prior to California’s.” Maryland’s proposal to move its date mentioned that “the change . . . will align the ‘cutoff’ date with most of the other states in the country.”

All involved in increasing the age of kindergartners — parents, legislatures and some teachers — say they have the best interests of children in mind. “If I had just one goal with this piece of legislation it would be to not humiliate a child,” Dale Folwell, the Republican North Carolina state representative who sponsored the birthday-cutoff bill, told me. “Our kids are younger when they’re taking the SAT, and they’re applying to the same colleges as the kids from Florida and Georgia.” Fair enough — governors and state legislators have competitive impulses, too. Still, the question remains: Is it better for children to start kindergarten later? And even if it’s better for a given child, is it good for children in general? Time out of school may not be a gift to all kids. For some it may be a burden, a financial stress on their parents and a chance, before they ever reach a classroom, to fall even further behind.

Redshirting is not a new phenomenon — in fact, the percentage of redshirted children has held relatively steady since education scholars started tracking the practice in the 1980s. Studies by the National Center for Education Statistics in the 1990s show that delayed-entry children made up somewhere between 6 and 9 percent of all kindergartners; a new study is due out in six months. As states roll back birthday cutoffs, there are more older kindergartners in general — and more redshirted kindergartners who are even older than the oldest kindergartners in previous years. Recently, redshirting has become a particular concern, because in certain affluent communities the numbers of kindergartners coming to school a year later are three or four times the national average. “Do you know what the number is in my district?” Representative Folwell, from a middle-class part of Winston-Salem, N.C., asked me. “Twenty-six percent.” In one kindergarten I visited in Los Altos, Calif. — average home price, $1 million — about one-quarter of the kids had been electively held back as well. Fred Morrison, a developmental psychologist at the University of Michigan who has studied the impact of falling on one side or the other of the birthday cutoff, sees the endless “graying of kindergarten,” as it’s sometimes called, as coming from a parental obsession not with their children’s academic accomplishment but with their social maturity. “You couldn’t find a kid who skips a grade these days,” Morrison told me. “We used to revere individual accomplishment. Now we revere self-esteem, and the reverence has snowballed in unconscious ways — into parents always wanting their children to feel good, wanting everything to be pleasant.” So parents wait an extra year in the hope that when their children enter school their age or maturity will shield them from social and emotional hurt. Elizabeth Levett Fortier, a kindergarten teacher in the George Peabody Elementary School in San Francisco, notices the impact on her incoming students. “I’ve had children come into my classroom, and they’ve never even lost at Candy Land.”

For years, education scholars have pointed out that most studies have found that the benefits of being relatively older than one’s classmates disappear after the first few years of school. In a literature review published in 2002, Deborah Stipek, dean of the Stanford school of education, found studies in which children who are older than their classmates not only do not learn more per grade but also tend to have more behavior problems. However, more recent research by labor economists takes advantage of new, very large data sets and has produced different results. A few labor economists do concur with the education scholarship, but most have found that while absolute age (how many days a child has been alive) is not so important, relative age (how old that child is in comparison to his classmates) shapes performance long after those few months of maturity should have ceased to matter. The relative-age effect has been found in schools around the world and also in sports. In one study published in the June 2005 Journal of Sport Sciences, researchers from Leuven, Belgium, and Liverpool, England, found that a disproportionate number of World Cup soccer players are born in January, February and March, meaning they were old relative to peers on youth soccer teams.

Before the school year started, Andersen, who is 54, taped up on the wall behind her desk a poster of a dog holding a bouquet of 12 balloons. In each balloon Andersen wrote the name of a month; under each month, the birthdays of the children in her class. Like most teachers, she understands that the small fluctuations among birth dates aren’t nearly as important as the vast range in children’s experiences at preschool and at home. But one day as we sat in her classroom, Andersen told me, “Every year I have two or three young ones in that August-to-October range, and they just struggle a little.” She used to encourage parents to send their children to kindergarten as soon as they were eligible, but she is now a strong proponent of older kindergartners, after teaching one child with a birthday just a few days before the cutoff. “She was always a step behind. It wasn’t effort and it wasn’t ability. She worked hard, her mom worked with her and she still was behind.” Andersen followed the girl’s progress through second grade (after that, she moved to a different school) and noticed that she didn’t catch up. Other teachers at Glen Arden Elementary and elsewhere have noticed a similar phenomenon: not always, but too often, the little ones stay behind.

The parents of the redshirted girl in Andersen’s class told a similar story. Five years ago, their older daughter had just made the kindergarten birthday cutoff by a few days, and they enrolled her. “She’s now a struggling fourth grader: only by the skin of her teeth has she been able to pass each year,” the girl’s mother, Stephanie Gandert, told me. “I kick myself every year now that we sent her ahead.” By contrast, their current kindergartner is doing just fine. “I always tell parents, ‘If you can wait, wait.’ If my kindergartner were in first grade right now, she’d be in trouble, too.” (The parents of the redshirted boy in Andersen’s class declined to be interviewed for this article but may very well have held him back because he’s small — even though he’s now one of the oldest, he’s still one of the shortest.)

Kelly Bedard, a labor economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, published a paper called “The Persistence of Early Childhood Maturity: International Evidence of Long-Run Age Effects” in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in November 2006 that looked at this phenomenon. “Obviously, when you’re 5, being a year older is a lot, and so we should expect kids who are the oldest in kindergarten to do better than the kids who are the youngest in kindergarten,” Bedard says. But what if relatively older kids keep doing better after the maturity gains of a few months should have ceased to matter? What if kids who are older relative to their classmates still have higher test scores in fourth grade, or eighth grade?

After crunching the math and science test scores for nearly a quarter-million students across 19 countries, Bedard found that relatively younger students perform 4 to 12 percentiles less well in third and fourth grade and 2 to 9 percentiles worse in seventh and eighth; and, as she notes, “by eighth grade it’s fairly safe to say we’re looking at long-term effects.” In British Columbia, she found that the relatively oldest students are about 10 percent more likely to be “university bound” than the relatively youngest ones. In the United States, she found that the relatively oldest students are 7.7 percent more likely to take the SAT or ACT, and are 11.6 percent more likely to enroll in four-year colleges or universities. (No one has yet published a study on age effects and SAT scores.) “One reason you could imagine age effects persist is that almost all of our education systems have ability-groupings built into them,” Bedard says. “Many claim they don’t, but they do. Everybody gets put into reading groups and math groups from very early ages.” Younger children are more likely to be assigned behind grade level, older children more likely to be assigned ahead. Younger children are more likely to receive diagnoses of attention-deficit disorder, too. “When I was in school the reading books all had colors,” Bedard told me. “They never said which was the high, the middle and the low, but everybody knew. Kids in the highest reading group one year are much more likely to be in the highest reading group the next. So you can imagine how that could propagate itself.”

Bedard found that different education systems produce varying age effects. For instance, Finland, whose students recently came out on top in an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development study of math, reading and science skills, experiences smaller age effects; Finnish children also start school later, at age 7, and even then the first few years are largely devoted to social development and play. Denmark, too, produces little difference between relatively older and younger kids; the Danish education system prohibits differentiating by ability until students are 16. Those two exceptions notwithstanding, Bedard notes that she found age effects everywhere, from “the Japanese system of automatic promotion, to the accomplishment-oriented French system, to the supposedly more flexible skill-based program models used in Canada and the United States.”

The relative value of being older for one’s grade is a particularly open secret in those sectors of the American schooling system that treat education like a competitive sport. Many private-school birthday cutoffs are set earlier than public-school dates; and children, particularly boys, who make the cutoff but have summer and sometimes spring birthdays are often placed in junior kindergarten — also called “transitional kindergarten,” a sort of holding tank for kids too old for more preschool — or are encouraged to wait a year to apply. Erika O’Brien, a SoHo mother who has two redshirted children at Grace Church, a pre-K-through-8 private school in Manhattan, told me about a conversation she had with a friend whose daughter was placed in junior kindergarten because she had a summer birthday. “I told her that it’s really a great thing. Her daughter is going to have a better chance of being at the top of her class, she’ll more likely be a leader, she’ll have a better chance of succeeding at sports. She’s got nothing to worry about for the next nine years. Plus, if you’re making a financial investment in school, it’s a less risky investment.”

Robert Fulghum listed life lessons in his 1986 best seller “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten.” Among them were:

Clean up your own mess.

Don’t take things that aren’t yours.

Wash your hands before you eat.

Take a nap every afternoon.

Flush.

Were he to update the book to reflect the experience of today’s children, he’d need to call it “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Preschool,” as kindergarten has changed. The half day devoted to fair play and nice manners officially began its demise in 1983, when the National Commission on Excellence in Education published “A Nation at Risk,” warning that the country faced a “rising tide of mediocrity” unless we increased school achievement and expectations. No Child Left Behind, in 2002, exacerbated the trend, pushing phonics and pattern-recognition worksheets even further down the learning chain. As a result, many parents, legislatures and teachers find the current curriculum too challenging for many older 4- and young 5-year-olds, which makes sense, because it’s largely the same curriculum taught to first graders less than a generation ago. Andersen’s kindergartners are supposed to be able to not just read but also write two sentences by the time they graduate from her classroom. It’s no wonder that nationwide, teachers now report that 48 percent of incoming kindergartners have difficulty handling the demands of school.

Friedrich Froebel, the romantic motherless son who started the first kindergarten in Germany in 1840, would be horrified by what’s called kindergarten today. He conceived the early learning experience as a homage to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who believed that “reading is the plague of childhood. . . . Books are good only for learning to babble about what one does not know.” Letters and numbers were officially banned from Froebel’s kindergartens; the teaching materials consisted of handmade blocks and games that he referred to as “gifts.” By the late 1800s, kindergarten had jumped to the United States, with Boston transcendentalists like Elizabeth Peabody popularizing the concept. Fairly quickly, letters and numbers appeared on the wooden blocks, yet Peabody cautioned that a “genuine” kindergarten is “a company of children under 7 years old, who do not learn to read, write and cipher” and a “false” kindergarten is one that accommodates parents who want their children studying academics instead of just playing.

That the social skills and exploration of one’s immediate world have been squeezed out of kindergarten is less the result of a pedagogical shift than of the accountability movement and the literal-minded reverse-engineering process it has brought to the schools. Curriculum planners no longer ask, What does a 5-year-old need? Instead they ask, If a student is to pass reading and math tests in third grade, what does that student need to be doing in the prior grades? Whether kindergarten students actually need to be older is a question of readiness, a concept that itself raises the question: Ready for what? The skill set required to succeed in Fulgham’s kindergarten — openness, creativity — is well matched to the capabilities of most 5-year-olds but also substantially different from what Andersen’s students need. In early 2000, the National Center for Education Statistics assessed 22,000 kindergartners individually and found, in general, that yes, the older children are better prepared to start an academic kindergarten than the younger ones. The older kids are four times as likely to be reading, and two to three times as likely to be able to decipher two-digit numerals. Twice as many older kids have the advanced fine motor skills necessary for writing. The older kids also have important noncognitive advantages, like being more persistent and more socially adept. Nonetheless, child advocacy groups say it’s the schools’ responsibility to be ready for the children, no matter their age, not the children’s to be prepared for the advanced curriculum. In a report on kindergarten, the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education wrote, “Most of the questionable entry and placement practices that have emerged in recent years have their genesis in concerns over children’s capacities to cope with the increasingly inappropriate curriculum in kindergarten.”

Furthermore, as Elizabeth Graue, a former kindergarten teacher who now studies school-readiness and redshirting at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, points out, “Readiness is a relative issue.” Studies of early-childhood teachers show they always complain about the youngest students, no matter their absolute age. ‘In Illinois it will be the March-April-May kids; in California, it will be October-November-December,” Graue says. “It’s really natural as a teacher to gravitate toward the kids who are easy to teach, especially when there’s academic pressure and the younger kids are rolling around the floor and sticking pencils in their ears.”

But perhaps those kids with the pencils in their ears — at least the less-affluent ones — don’t need “the gift of time” but rather to be brought into the schools. Forty-two years after Lyndon Johnson inaugurated Head Start, access to quality early education still highly correlates with class; and one serious side effect of pushing back the cutoffs is that while well-off kids with delayed enrollment will spend another year in preschool, probably doing what kindergartners did a generation ago, less-well-off children may, as the literacy specialist Katie Eller put it, spend “another year watching TV in the basement with Grandma.” What’s more, given the socioeconomics of redshirting — and the luxury involved in delaying for a year the free day care that is public school — the oldest child in any given class is more likely to be well off and the youngest child is more likely to be poor. “You almost have a double advantage coming to the well-off kids,” says Samuel J. Meisels, president of Erikson Institute, a graduate school in child development in Chicago. “From a public-policy point of view I find this very distressing.”

Nobody has exact numbers on what percentage of the children eligible for publicly financed preschool are actually enrolled — the individual programs are legion, and the eligibility requirements are complicated and varied — but the best guess from the National Institute for Early Education Research puts the proportion at only 25 percent. In California, for instance, 76 percent of publicly financed preschool programs have waiting lists, which include over 30,000 children. In Pennsylvania, 35 percent of children eligible for Head Start are not served. A few states do have universal preschool, and among Hillary Clinton’s first broad domestic policy proposals as a Democratic presidential candidate was to call for universal pre-kindergarten classes. But at the moment, free high-quality preschool for less-well-to-do children is spotty, and what exists often is aimed at extremely low-income parents, leaving out the children of the merely strapped working or lower-middle class. Nor, as a rule, do publicly financed programs take kids who are old enough to be eligible for kindergarten, meaning redshirting is not a realistic option for many.

One morning, when I was sitting in Elizabeth Levett Fortier’s kindergarten classroom in the Peabody School in San Francisco — among a group of students that included some children who had never been to preschool, some who were just learning English and some who were already reading — a father dropped by to discuss whether or not to enroll his fall-birthday daughter or give her one more year at her private preschool. Demographically speaking, any child with a father willing to call on a teacher to discuss if it’s best for that child to spend a third year at a $10,000-a-year preschool is going to be fine. Andersen told me, “I’ve had parents tell me that the preschool did not recommend sending their children on to kindergarten yet, but they had no choice,” as they couldn’t afford not to. In 49 out of 50 states, the average annual cost of day care for a 4-year-old in an urban area is more than the average annual public college tuition. A RAND Corporation position paper suggests policy makers may need to view “entrance-age policies and child-care polices as a package.”

Labor economists, too, make a strong case that resources should be directed at disadvantaged children as early as possible, both for the sake of improving each child’s life and because of economic return. Among the leaders in this field is James Heckman, a University of Chicago economist who won the Nobel in economic science in 2000. In many papers and lectures on poor kids, he now includes a simple graph that plots the return on investment in human capital across age. You can think of the accumulation of human capital much like the accumulation of financial capital in an account bearing compound interest: if you add your resources as soon as possible, they’ll be worth more down the line. Heckman’s graph looks like a skateboard quarter-pipe, sloping precipitously from a high point during the preschool years, when the return on investment in human capital is very high, down the ramp and into the flat line after a person is no longer in school, when the return on investment is minimal. According to Heckman’s analysis, if you have limited funds to spend it makes the most economic sense to spend them early. The implication is that if poor children aren’t in adequate preschool programs, rolling back the age of kindergarten is a bad idea economically, as it pushes farther down the ramp the point at which we start investing funds and thus how productive those funds will be.

Bedard and other economists cite Heckman’s theories of how people acquire skills to help explain the persistence of relative age on school performance. Heckman writes: “Skill begets skill; motivation begets motivation. Early failure begets later failure.” Reading experts know that it’s easier for a child to learn the meaning of a new word if he knows the meaning of a related word and that a good vocabulary at age 3 predicts a child’s reading well in third grade. Skills like persistence snowball, too. One can easily see how the skill-begets-skill, motivation-begets-motivation dynamic plays out in a kindergarten setting: a child who comes in with a good vocabulary listens to a story, learns more words, feels great about himself and has an even better vocabulary at the end of the day. Another child arrives with a poor vocabulary, listens to the story, has a hard time following, picks up fewer words, retreats into insecurity and leaves the classroom even further behind.

How to address the influence of age effects is unclear. After all, being on the older or younger side of one’s classmates is mostly the luck of the birthday draw, and no single birthday cutoff can prevent a 12-month gap in age. States could try to prevent parents from gaming the age effects by outlawing redshirting — specifically by closing the yearlong window that now exists in most states between the birthday cutoffs and compulsory schooling. But forcing families to enroll children in kindergarten as soon as they are eligible seems too authoritarian for America’s tastes. States could also decide to learn from Finland — start children in school at age 7 and devote the first year to play — but that would require a major reversal, making second grade the old kindergarten, instead of kindergarten the new first grade. States could also emulate Denmark, forbidding ability groupings until late in high school, but unless very serious efforts are made to close the achievement gap before children arrive at kindergarten, that seems unlikely, too.

Of course there’s also the reality that individual children will always mature at different rates, and back in Andersen’s classroom, on a Thursday when this year’s kindergartners stayed home and next year’s kindergartners came in for pre-enrollment assessments, the developmental differences between one future student and the next were readily apparent. To gauge kindergarten readiness, Andersen and another kindergarten teacher each sat the children down one by one for a 20-minute test. The teachers asked the children, among other things, to: skip; jump; walk backward; cut out a diamond on a dotted line; copy the word cat; draw a person; listen to a story; and answer simple vocabulary questions like what melts, what explodes and what flies. Some of the kids were dynamos. When asked to explain the person he had drawn, one boy said: “That’s Miss Maple. She’s my preschool teacher, and she’s crying because she’s going to miss me so much next year.” Another girl said at one point, “Oh, you want me to write the word cat?” Midmorning, however, a little boy who will not turn 5 until this summer arrived. His little feet dangled off the kindergarten chair, as his legs were not long enough to reach the floor. The teacher asked him to draw a person. To pass that portion of the test, his figure needed seven different body parts.

“Is that all he needs?” she asked a few minutes later.

The boy said, “Oh, I forgot the head.”

A minute later the boy submitted his drawing again. “Are you sure he doesn’t need anything else?” the teacher asked.

The boy stared at his work. “I forgot the legs. Those are important, aren’t they?”

The most difficult portion of the test for many of the children was a paper-folding exercise. “Watch how I fold my paper,” the teacher told the little boy. She first folded her 8 1/2-by-11-inch paper in half the long way, to create a narrow rectangle, and then she folded the rectangle in thirds, to make something close to a square.

“Can you do it?” she asked the boy.

He took the paper eagerly, but folded it in half the wrong way. Depending on the boy’s family’s finances, circumstances and mind-set, his parents may decide to hold him out a year so he’ll be one of the oldest and, presumably, most confident. Or they may decide to enroll him in school as planned. He may go to college or he may not. He may be a leader or a follower. Those things will ultimately depend more on the education level achieved by his mother, whether he lives in a two-parent household and the other assets and obstacles he brings with him to school each day. Still, the last thing any child needs is to be outmaneuvered by other kids’ parents as they cut to the back of the birthday line to manipulate age effects. Eventually, the boy put his head down on the table. His first fold had set a course, and even after trying gamely to fold the paper again in thirds, he couldn’t create the right shape.

Elizabeth Weil is a contributing writer for the magazine. Her most recent article was about lethal injection.

"Universals" are those things and practices that have shared characteristics:

View these videos and then read the NY Times article on early childhood education:

And if you really want some food for thought, read Michael Foucalt's "Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison," on the subtle effects and mechanizisms of social and political power that form the "fundamental" principles underlying educational, military, and prison systems of "discplinary power".

NYTimes

June 3, 2007

When Should a Kid Start Kindergarten?

By ELIZABETH WEIL

According to the apple-or-coin test, used in the Middle Ages, children should start school when they are mature enough for the delayed gratification and abstract reasoning involved in choosing money over fruit. In 15th- and 16th-century Germany, parents were told to send their children to school when the children started to act “rational.” And in contemporary America, children are deemed eligible to enter kindergarten according to an arbitrary date on the calendar known as the birthday cutoff — that is, when the state, or in some instances the school district, determines they are old enough. The birthday cutoffs span six months, from Indiana, where a child must turn 5 by July 1 of the year he enters kindergarten, to Connecticut, where he must turn 5 by Jan. 1 of his kindergarten year. Children can start school a year late, but in general they cannot start a year early. As a result, when the 22 kindergartners entered Jane Andersen’s class at the Glen Arden Elementary School near Asheville, N.C., one warm April morning, each brought with her or him a snack and a unique set of gifts and challenges, which included for some what’s referred to in education circles as “the gift of time.”

After the morning announcements and the Pledge of Allegiance, Andersen’s kindergartners sat down on a blue rug. Two, one boy and one girl, had been redshirted — the term, borrowed from sports, describes students held out for a year by their parents so that they will be older, or larger, or more mature, and thus better prepared to handle the increased pressures of kindergarten today. Six of Andersen’s pupils, on the other hand, were quite young, so young that they would not be enrolled in kindergarten at all if North Carolina succeeds in pushing back its birthday cutoff from Oct. 16 to Aug. 31.

Andersen is a willowy 11-year teaching veteran who offered up a lot of education in the first hour of class. First she read Leo Lionni’s classic children’s book “An Extraordinary Egg,” and directed a conversation about it. Next she guided the students through: writing a letter; singing a song; solving an addition problem; two more songs; and a math game involving counting by ones, fives and tens using coins. Finally, Andersen read them another Lionni book. Labor economists who study what’s called the accumulation of human capital — how we acquire the knowledge and skills that make us valuable members of society — have found that children learn vastly different amounts from the same classroom experiences and that those with certain advantages at the outset are able to learn more, more quickly, causing the gap between students to increase over time. Gaps in achievement have many causes, but a major one in any kindergarten room is age. Almost all kindergarten classrooms have children with birthdays that span 12 months. But because of redshirting, the oldest student in Andersen’s class is not just 12 but 15 months older than the youngest, a difference in age of 25 percent.

After rug time, Andersen’s kindergartners walked single-file to P.E. class, where the children sat on the curb alongside the parking circle, taking turns running laps for the Presidential Fitness Test. By far the fastest runner was the girl in class who had been redshirted. She strode confidently, with great form, while many of the smaller kids could barely run straight. One of the younger girls pointed out the best artist in the class, a freckly redhead. I’d already noted his beautiful penmanship. He had been redshirted as well.

States, too, are trying to embrace the advantages of redshirting. Since 1975, nearly half of all states have pushed back their birthday cutoffs and four — California, Michigan, North Carolina and Tennessee — have active legislation in state assemblies to do so right now. (Arkansas passed legislation earlier this spring; New Jersey, which historically has let local districts establish their birthday cutoffs, has legislation pending to make Sept. 1 the cutoff throughout the state.) This is due, in part, to the accountability movement — the high-stakes testing now pervasive in the American educational system. In response to this testing, kindergartens across the country have become more demanding: if kids must be performing on standardized tests in third grade, then they must be prepping for those tests in second and first grades, and even at the end of kindergarten, or so the thinking goes. The testing also means that states, like students, now get report cards, and they want their children to do well, both because they want them to be educated and because they want them to stack up favorably against their peers.

Indeed, increasing the average age of the children in a kindergarten class is a cheap and easy way to get a small bump in test scores, because older children perform better, and states’ desires for relative advantage is written into their policy briefs. The California Performance Review, commissioned by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2004, suggested moving California’s birthday cutoff three months earlier, to Sept. 1 from Dec. 2, noting that “38 states, including Florida and Texas, have kindergarten entry dates prior to California’s.” Maryland’s proposal to move its date mentioned that “the change . . . will align the ‘cutoff’ date with most of the other states in the country.”

All involved in increasing the age of kindergartners — parents, legislatures and some teachers — say they have the best interests of children in mind. “If I had just one goal with this piece of legislation it would be to not humiliate a child,” Dale Folwell, the Republican North Carolina state representative who sponsored the birthday-cutoff bill, told me. “Our kids are younger when they’re taking the SAT, and they’re applying to the same colleges as the kids from Florida and Georgia.” Fair enough — governors and state legislators have competitive impulses, too. Still, the question remains: Is it better for children to start kindergarten later? And even if it’s better for a given child, is it good for children in general? Time out of school may not be a gift to all kids. For some it may be a burden, a financial stress on their parents and a chance, before they ever reach a classroom, to fall even further behind.

Redshirting is not a new phenomenon — in fact, the percentage of redshirted children has held relatively steady since education scholars started tracking the practice in the 1980s. Studies by the National Center for Education Statistics in the 1990s show that delayed-entry children made up somewhere between 6 and 9 percent of all kindergartners; a new study is due out in six months. As states roll back birthday cutoffs, there are more older kindergartners in general — and more redshirted kindergartners who are even older than the oldest kindergartners in previous years. Recently, redshirting has become a particular concern, because in certain affluent communities the numbers of kindergartners coming to school a year later are three or four times the national average. “Do you know what the number is in my district?” Representative Folwell, from a middle-class part of Winston-Salem, N.C., asked me. “Twenty-six percent.” In one kindergarten I visited in Los Altos, Calif. — average home price, $1 million — about one-quarter of the kids had been electively held back as well. Fred Morrison, a developmental psychologist at the University of Michigan who has studied the impact of falling on one side or the other of the birthday cutoff, sees the endless “graying of kindergarten,” as it’s sometimes called, as coming from a parental obsession not with their children’s academic accomplishment but with their social maturity. “You couldn’t find a kid who skips a grade these days,” Morrison told me. “We used to revere individual accomplishment. Now we revere self-esteem, and the reverence has snowballed in unconscious ways — into parents always wanting their children to feel good, wanting everything to be pleasant.” So parents wait an extra year in the hope that when their children enter school their age or maturity will shield them from social and emotional hurt. Elizabeth Levett Fortier, a kindergarten teacher in the George Peabody Elementary School in San Francisco, notices the impact on her incoming students. “I’ve had children come into my classroom, and they’ve never even lost at Candy Land.”

For years, education scholars have pointed out that most studies have found that the benefits of being relatively older than one’s classmates disappear after the first few years of school. In a literature review published in 2002, Deborah Stipek, dean of the Stanford school of education, found studies in which children who are older than their classmates not only do not learn more per grade but also tend to have more behavior problems. However, more recent research by labor economists takes advantage of new, very large data sets and has produced different results. A few labor economists do concur with the education scholarship, but most have found that while absolute age (how many days a child has been alive) is not so important, relative age (how old that child is in comparison to his classmates) shapes performance long after those few months of maturity should have ceased to matter. The relative-age effect has been found in schools around the world and also in sports. In one study published in the June 2005 Journal of Sport Sciences, researchers from Leuven, Belgium, and Liverpool, England, found that a disproportionate number of World Cup soccer players are born in January, February and March, meaning they were old relative to peers on youth soccer teams.

Before the school year started, Andersen, who is 54, taped up on the wall behind her desk a poster of a dog holding a bouquet of 12 balloons. In each balloon Andersen wrote the name of a month; under each month, the birthdays of the children in her class. Like most teachers, she understands that the small fluctuations among birth dates aren’t nearly as important as the vast range in children’s experiences at preschool and at home. But one day as we sat in her classroom, Andersen told me, “Every year I have two or three young ones in that August-to-October range, and they just struggle a little.” She used to encourage parents to send their children to kindergarten as soon as they were eligible, but she is now a strong proponent of older kindergartners, after teaching one child with a birthday just a few days before the cutoff. “She was always a step behind. It wasn’t effort and it wasn’t ability. She worked hard, her mom worked with her and she still was behind.” Andersen followed the girl’s progress through second grade (after that, she moved to a different school) and noticed that she didn’t catch up. Other teachers at Glen Arden Elementary and elsewhere have noticed a similar phenomenon: not always, but too often, the little ones stay behind.

The parents of the redshirted girl in Andersen’s class told a similar story. Five years ago, their older daughter had just made the kindergarten birthday cutoff by a few days, and they enrolled her. “She’s now a struggling fourth grader: only by the skin of her teeth has she been able to pass each year,” the girl’s mother, Stephanie Gandert, told me. “I kick myself every year now that we sent her ahead.” By contrast, their current kindergartner is doing just fine. “I always tell parents, ‘If you can wait, wait.’ If my kindergartner were in first grade right now, she’d be in trouble, too.” (The parents of the redshirted boy in Andersen’s class declined to be interviewed for this article but may very well have held him back because he’s small — even though he’s now one of the oldest, he’s still one of the shortest.)

Kelly Bedard, a labor economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, published a paper called “The Persistence of Early Childhood Maturity: International Evidence of Long-Run Age Effects” in The Quarterly Journal of Economics in November 2006 that looked at this phenomenon. “Obviously, when you’re 5, being a year older is a lot, and so we should expect kids who are the oldest in kindergarten to do better than the kids who are the youngest in kindergarten,” Bedard says. But what if relatively older kids keep doing better after the maturity gains of a few months should have ceased to matter? What if kids who are older relative to their classmates still have higher test scores in fourth grade, or eighth grade?

After crunching the math and science test scores for nearly a quarter-million students across 19 countries, Bedard found that relatively younger students perform 4 to 12 percentiles less well in third and fourth grade and 2 to 9 percentiles worse in seventh and eighth; and, as she notes, “by eighth grade it’s fairly safe to say we’re looking at long-term effects.” In British Columbia, she found that the relatively oldest students are about 10 percent more likely to be “university bound” than the relatively youngest ones. In the United States, she found that the relatively oldest students are 7.7 percent more likely to take the SAT or ACT, and are 11.6 percent more likely to enroll in four-year colleges or universities. (No one has yet published a study on age effects and SAT scores.) “One reason you could imagine age effects persist is that almost all of our education systems have ability-groupings built into them,” Bedard says. “Many claim they don’t, but they do. Everybody gets put into reading groups and math groups from very early ages.” Younger children are more likely to be assigned behind grade level, older children more likely to be assigned ahead. Younger children are more likely to receive diagnoses of attention-deficit disorder, too. “When I was in school the reading books all had colors,” Bedard told me. “They never said which was the high, the middle and the low, but everybody knew. Kids in the highest reading group one year are much more likely to be in the highest reading group the next. So you can imagine how that could propagate itself.”

Bedard found that different education systems produce varying age effects. For instance, Finland, whose students recently came out on top in an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development study of math, reading and science skills, experiences smaller age effects; Finnish children also start school later, at age 7, and even then the first few years are largely devoted to social development and play. Denmark, too, produces little difference between relatively older and younger kids; the Danish education system prohibits differentiating by ability until students are 16. Those two exceptions notwithstanding, Bedard notes that she found age effects everywhere, from “the Japanese system of automatic promotion, to the accomplishment-oriented French system, to the supposedly more flexible skill-based program models used in Canada and the United States.”

The relative value of being older for one’s grade is a particularly open secret in those sectors of the American schooling system that treat education like a competitive sport. Many private-school birthday cutoffs are set earlier than public-school dates; and children, particularly boys, who make the cutoff but have summer and sometimes spring birthdays are often placed in junior kindergarten — also called “transitional kindergarten,” a sort of holding tank for kids too old for more preschool — or are encouraged to wait a year to apply. Erika O’Brien, a SoHo mother who has two redshirted children at Grace Church, a pre-K-through-8 private school in Manhattan, told me about a conversation she had with a friend whose daughter was placed in junior kindergarten because she had a summer birthday. “I told her that it’s really a great thing. Her daughter is going to have a better chance of being at the top of her class, she’ll more likely be a leader, she’ll have a better chance of succeeding at sports. She’s got nothing to worry about for the next nine years. Plus, if you’re making a financial investment in school, it’s a less risky investment.”

Robert Fulghum listed life lessons in his 1986 best seller “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten.” Among them were:

Clean up your own mess.

Don’t take things that aren’t yours.

Wash your hands before you eat.

Take a nap every afternoon.

Flush.

Were he to update the book to reflect the experience of today’s children, he’d need to call it “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Preschool,” as kindergarten has changed. The half day devoted to fair play and nice manners officially began its demise in 1983, when the National Commission on Excellence in Education published “A Nation at Risk,” warning that the country faced a “rising tide of mediocrity” unless we increased school achievement and expectations. No Child Left Behind, in 2002, exacerbated the trend, pushing phonics and pattern-recognition worksheets even further down the learning chain. As a result, many parents, legislatures and teachers find the current curriculum too challenging for many older 4- and young 5-year-olds, which makes sense, because it’s largely the same curriculum taught to first graders less than a generation ago. Andersen’s kindergartners are supposed to be able to not just read but also write two sentences by the time they graduate from her classroom. It’s no wonder that nationwide, teachers now report that 48 percent of incoming kindergartners have difficulty handling the demands of school.

Friedrich Froebel, the romantic motherless son who started the first kindergarten in Germany in 1840, would be horrified by what’s called kindergarten today. He conceived the early learning experience as a homage to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who believed that “reading is the plague of childhood. . . . Books are good only for learning to babble about what one does not know.” Letters and numbers were officially banned from Froebel’s kindergartens; the teaching materials consisted of handmade blocks and games that he referred to as “gifts.” By the late 1800s, kindergarten had jumped to the United States, with Boston transcendentalists like Elizabeth Peabody popularizing the concept. Fairly quickly, letters and numbers appeared on the wooden blocks, yet Peabody cautioned that a “genuine” kindergarten is “a company of children under 7 years old, who do not learn to read, write and cipher” and a “false” kindergarten is one that accommodates parents who want their children studying academics instead of just playing.

That the social skills and exploration of one’s immediate world have been squeezed out of kindergarten is less the result of a pedagogical shift than of the accountability movement and the literal-minded reverse-engineering process it has brought to the schools. Curriculum planners no longer ask, What does a 5-year-old need? Instead they ask, If a student is to pass reading and math tests in third grade, what does that student need to be doing in the prior grades? Whether kindergarten students actually need to be older is a question of readiness, a concept that itself raises the question: Ready for what? The skill set required to succeed in Fulgham’s kindergarten — openness, creativity — is well matched to the capabilities of most 5-year-olds but also substantially different from what Andersen’s students need. In early 2000, the National Center for Education Statistics assessed 22,000 kindergartners individually and found, in general, that yes, the older children are better prepared to start an academic kindergarten than the younger ones. The older kids are four times as likely to be reading, and two to three times as likely to be able to decipher two-digit numerals. Twice as many older kids have the advanced fine motor skills necessary for writing. The older kids also have important noncognitive advantages, like being more persistent and more socially adept. Nonetheless, child advocacy groups say it’s the schools’ responsibility to be ready for the children, no matter their age, not the children’s to be prepared for the advanced curriculum. In a report on kindergarten, the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education wrote, “Most of the questionable entry and placement practices that have emerged in recent years have their genesis in concerns over children’s capacities to cope with the increasingly inappropriate curriculum in kindergarten.”

Furthermore, as Elizabeth Graue, a former kindergarten teacher who now studies school-readiness and redshirting at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, points out, “Readiness is a relative issue.” Studies of early-childhood teachers show they always complain about the youngest students, no matter their absolute age. ‘In Illinois it will be the March-April-May kids; in California, it will be October-November-December,” Graue says. “It’s really natural as a teacher to gravitate toward the kids who are easy to teach, especially when there’s academic pressure and the younger kids are rolling around the floor and sticking pencils in their ears.”